You are here

Preparing for A-MAVEN Science!

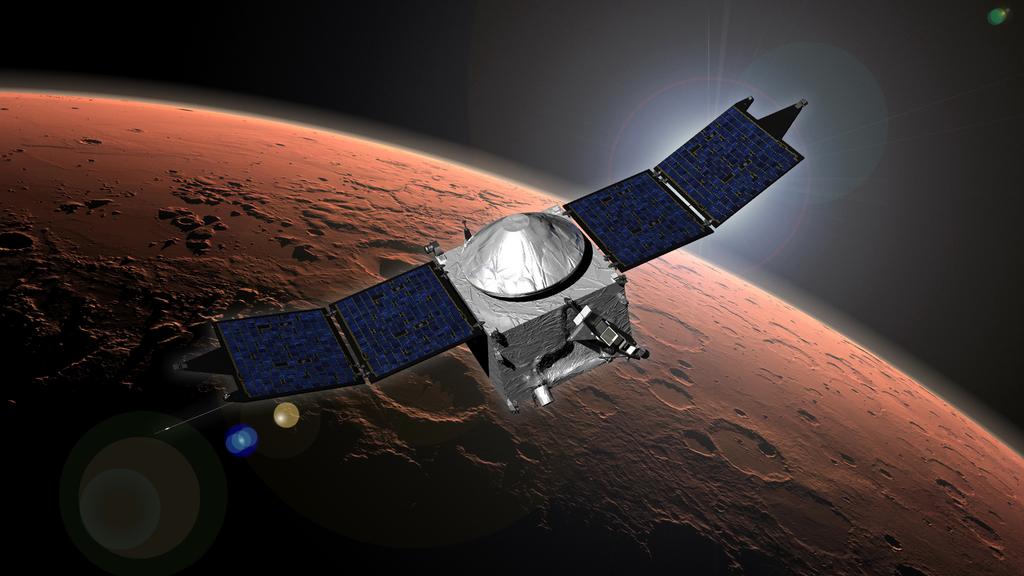

A couple of days ago we received the great news that we have a new member of the Mars Orbiter family: MAVEN. The Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution Mission (MAVEN) spacecraft successfully entered orbit around Mars on September 21st, 2014, marking the beginning of an extremely exciting mission that promises to unlock many of the secrets of the Martian atmosphere.

Before MAVEN can get started on its primary science mission, it must first undergo a fairly lengthy “checkout” period in which all of its instruments are tested and calibrated, and the overall health and operational status of the spacecraft is determined. This is a very standard procedure for pretty much all space missions, and can last for weeks or even months depending on the complexity of the spacecraft. These checkout periods are crucially important, and instrument teams generally won’t interrupt them unless an extremely compelling case can be made for doing so. For MAVEN, just such a compelling case has been made: comet C/2013 A1 (Siding Spring)!

When comet Siding Spring buzzes past Mars in October, almost the entire fleet of Mars spacecraft and rovers are going to attempt observations of some kind. The fleet has two primary goals: first is simply to survive, and second is to get good science. The first one is pretty much wrapped up already; we are quite confident that the spacecraft are not in danger from dust, but as a precautionary measure their orbits are being phased (timed) such that they will be in Mars’ “shadow” at time of predicted peak dust impacts. So this means they can focus on the second goal, which is broadly labeled as “get good science” but itself broken down into two separate parts: study the comet’s nucleus and coma; and study the comet’s impact on the Mars atmosphere. The addition of MAVEN to the crowd is a huge and timely bonus for addressing the science goals.

In both of our August 11, 2014 and September 19, 2014 CIOC meetings, we heard from the MAVEN team about their plans to interrupt MAVEN’s checkout in order to observe both the comet itself, and the Martian atmosphere as it responds to the comet. So in this post I want to very briefly outline the observations MAVEN will make and try and underscore the point of how freakin' awesome the timing of this whole event seems to be! Note that most of this information came from the presentation given at the first CIOC Siding Spring workshop, the PDF of which you can download, and the video of which you can watch online [starts at ~55:00].

Recall: comets are rocky, icy chunks of leftover material from the formation of our solar system over four billion years ago. As they travel through the inner solar system, sunlight (radiation) causes the trapped ices to sublimate (turn directly to gas), releasing not only these gases but also pieces of ice, dust, rock, etc, that was bound by ice. The released material surrounds and trails the comet, giving them their characteristic appearance of a fuzzy head (coma) and a long arcing tail. The main body of the comet itself – the nucleus – may only be a few kilometers or so in diameter, but the tail can stretch out of millions of kilometers, and the dusty, gassy coma hundreds of thousands of kilometers or more. [Unit conversion note: just substitute "miles" for "kilometers" here based on your preference - it's all a ballpark estimate.]

We’ve established that any dust from Comet Siding Spring that reaches Mars’ atmosphere will sparse in number. Chances are that Mars will encounter no more dust than it does on any other given day of the year. But while Mars might avoid the dust, it most certainly will NOT avoid the gas coma that surrounds the comet and extends well beyond the close approach distance of 138,000km (86,000 miles). So what will happen when Mars relatively dense CO2-rich atmosphere collides at 56km/s (125,000mph) with the rather sparse gas atmosphere of the comet? Well, we’re really not sure... but MAVEN will be watching, and will be able to tell us!

MAVEN is designed primarily to study the Martian upper atmosphere, and this is exactly what the comet is most likely to influence, so right off the bat we have a perfect coupling between these two. As the two gassy atmospheres collide, there will almost certainly be perturbations in the compositions of gases, ions, and electrons, as well as thermal and CO2 density changes (kind of like waves) in the upper atmosphere, which in turn might then lead to changes in circulation in the Martian atmosphere. Finally, if enough comet dust reaches the atmosphere, this could result in excess or metallic ions in the atmosphere. This latter effect is something seen in other planets but we’re not sure of its origin and if/how it related to meteoric input, for example. This might settle that issue.

I could get deeper into science jargon but the bottom line here is that MAVEN is designed specifically for studying the stuff that the comet – by pure coincidence – is going to be affecting and altering. The spacecraft will be able to tell us exactly how, when and ultimately why, these influences occur, and will be a fantastic reference point for understanding the Martian atmosphere, and how planetary atmospheres in general react to meteor and dust input. (This is really a spectacularly good coincidence – I just can’t emphasize that enough!)

Referring back to what I wrote earlier, MAVEN will also study the comet itself. The spacecraft has a bunch of instruments that are designed to look at a gassy atmosphere, and the interaction of the solar wind with that gassy atmosphere. The comet has a huge gassy atmosphere and thus it is again a perfect fit that MAVEN can simply study at the comet’s gassy atmosphere as if it were Mars! Specifically but briefly, four separate instruments should be able to study the energetic ions and electrons that are produced by the solar wind interacting with the comet coma. In addition to that, the MAVEN instruments that make measurements of the solar wind itself should be able to detect perturbations caused by the comet. You can think of this latter effect as standing downstream of a large boulder in a river and feeling how the currents change due to that solid object upstream.

Finally, it should also be possible for MAVEN to make ultraviolet (UV) observations of the comet’s emission, which will help us understand the chemistry and composition of the comet. The main species it will see are H, O, C, N, CO and OH, which are frequently seen in UV observations of comets, but will offer tremendous support of other ground and space-based observations of the comet. One of the more interesting prospects here is the measurement of the so-called D-to-H (“D/H”) ratio, which is the ratio between deuterium (heavy hydrogen, or 2H) and hydrogen (1H). Roughly speaking, the D/H ratio can be used to get information about where objects in the solar system formed, based in part on our knowledge of D/H in planets, and give us information about the water contained in these bodies and the origins of that. It’s a very fundamental measurement that’s used in not only astronomy, but geology too (including planetary geology), and one that we hope will help address whether comets played a role in bringing water to Earth.

So the bottom line of all this is that by pure chance and fantastic luck, a spacecraft designed to study a gassy atmosphere in the solar wind has just been placed right next to two gassy atmospheres in the solar wind that are about to collide (sort of). It’s truly a Hollywood script for comet and Mars scientists!

There was always the concern that MAVEN’s orbit insertion wouldn’t go quite as planned, and this would have likely cancelled the comet observations. But the orbit insertion was flawless (well, duh!) and we are all set for some A-MAVEN science! The spacecraft has a couple of smaller milestones to get through, including a small orbit correction to make sure it’s safely protected by Mars during the comet’s close approach. After that, the fun really begins on October 17 when MAVEN takes its first observations of the comet using its IUVS (ultraviolet spectrometer) instrument. This will mark the beginning of a busy, exciting and quite possibly ground-breaking four days of observations by MAVEN. I'm guessing it will probably take some time before they are able to provide any definitive results to us – these things take time, and this is a completely new spacecraft they’re playing with, so I doubt they have automatic procedures in place to crunch out numbers real quick. I'm not involved with these particular missions though, so don't take my word on that. Either way, just be sure to follow the CIOC, the JPL Mars, and the MAVEN websites, where I’m sure announcements will be made as soon as possible.

Keep up-to-date on the latest Siding Spring and sungrazing comet news via my @SungrazerComets Twitter feed. All opinions stated on there, and in these blog posts, are entirely my own, and not necessarily those of NASA or the Naval Research Lab.

-

- Karl Battams's blog

- Log in to post comments